WestConn was then known as the Danbury Normal School. They seem to have had a good time!

See the 1924 Yearbook digitized by Ian Hendrie, ’27.

Western Connecticut State University Archives and Special Collections

Documenting the history of WestConn and its surrounding area | Intra veritatem invenire | Established 1977

WestConn was then known as the Danbury Normal School. They seem to have had a good time!

See the 1924 Yearbook digitized by Ian Hendrie, ’27.

William Devlin, WestConn grad and author of We Crown Them All, and Danbury’s Third Century (with Herb Janick), wrote a piece for the News-Times in February 2000 about Samuel L. Brooks. In the story, Devlin identifies Brooks as Danbury High School’s first Black graduate. Brooks not only graduated, but was essentially the valedictorian of his small 1893 graduating class, went on to attend Phillips-Andover Academy in Massachusetts and later attended Yale.

William Devlin, WestConn grad and author of We Crown Them All, and Danbury’s Third Century (with Herb Janick), wrote a piece for the News-Times in February 2000 about Samuel L. Brooks. In the story, Devlin identifies Brooks as Danbury High School’s first Black graduate. Brooks not only graduated, but was essentially the valedictorian of his small 1893 graduating class, went on to attend Phillips-Andover Academy in Massachusetts and later attended Yale.

Devlin also uncovered information about Brook’s father, William, who owned a barber shop at 43 Elm Street in Danbury and was a Civil War veteran in the 2nd U.S. Colored Infantry that served most of the War on the Gulf Coast. According to his draft registration in 1917, he had been a sergeant. He and his wife Julia appear to have had one child.(William Brooks is listed as ‘W’ for white in the 1910 census).

His son Samuel’s graduation, academic standing and perceived promise were of such note that he earned mention in the Newtown Bee (shown below, June 30, 1893, Chronicling America).

However, as Devlin noted in his 2000 article: “he began his freshman year at Yale, but what happened to him after that is a big question mark. One that perhaps will be answered in time.”

We took up the twenty-three-year-old challenge, and though we didn’t answer all the questions about Samuel Leon Brooks, we did find out some of what became of this promising Danburian.

First, we think we found a picture of him from a Phillips-Andover Academy yearbook of 1899 (https://phillipsacademyarchives.net/publications/phillips-academy-digital-collections/pot-pourri-1893-2013/):

In that same yearbook, a Samuel L. Brooks is mentioned belonging to a secret society, the Inquiry Club, and the Forum. His senior quote is quite disturbing: “I was nearly lynched once myself.”

If he is the same Samuel L. Brooks of Danbury, and it appears that he is, his road to Yale was a long one – five or six years, and once there, it appears he did not stay for long.

In Anson Phelps Stokes’ Directory of the Living Non-graduates of Yale University (United States: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Company, 1910). Brooks is listed as attending Yale 1898 and 1899 in the non-graduates directory. The Yale Yearbook shows him enrolled as a student in 1899 (he was 23) and living at 107 1/2 Day Street in New Haven.

In the 1900 and 1901 Danbury directories, Brooks is listed as a law student. At the same time, it appears that he married Lucy Carr Brooks in Bridgeport (according to the 1910 Census and https://www.ctatatelibrarydata.org/marriage-records/). By 1910, Lucy and Samuel were working as servants in Hartford for Dr. George R. Miller, his wife and daughter. That same year, the Brooks’ daughter, Julia, born in 1903 lived with James and Ada Gordon in East Hartford (according to the “Mother’s side” family tree, Ancestry.com). Lucy and Samuel appear to have split up after 1910.

In 1917, Brooks registered for the draft, listing his address as 123 South Street in Hartford. Shown here from a Google Maps image. In 1918, his father died.

Brooks was at this point working as a waiter at the Hartford Club. Perhaps with high hopes that his daughter might herself find greener pastures through education, Julia, at the age of 17, was listed as attending the Hampton Institute in Virginia in 1920. She is listed in that year’s Census as ‘Mulatto.’

Brooks was at this point working as a waiter at the Hartford Club. Perhaps with high hopes that his daughter might herself find greener pastures through education, Julia, at the age of 17, was listed as attending the Hampton Institute in Virginia in 1920. She is listed in that year’s Census as ‘Mulatto.’

Four years later, it appears that Samuel married a Rhoda Diggs (according to the “Mother’s side” family tree, Ancestry.com), and the next year, Lucy Carr Brooks passed away in Hartford.

The 1925 death of Mrs. Lucy Carr Brooks of 38 Fairmount street reportedly came at the end of several months of illness. She had been the youngest daughter of Mrs. Julia Carr Pierce and the late George H. Carr, and had been born in Hartford, January 6. 1879. Samuel Brooks is not mentioned in the death announcement in the Hartford Courant.

In 1927, upon receiving a letter from James Wright, who was compiling a 1902 Yale Class Book to mark the 25th graduation anniversary, Samuel responded with a hand written note. Though he appreciated the invitation, he informed Wright: “I still have no intention of appearing in the ‘Class Book.'” He went on to eloquently reflect on his education and life:

“I am intensely interested in the doings of ’02’ both collectively and individually and shall always have a warm spot in my heart for my alma mater, but I am one of her wayward sons who left her too soon to merit recognition, but thank God not too soon to have absorbed some of her ideals and traditions. And so while I feel ineligible to appear in the ‘Class Book,’ I am happy to be counted as one of her friends and supporters. My life has fallen in humble paths and a sense of the [fitness] of things prevents me from intruding where I feel I have no place. It is impossible to overestimate the value to me of my associations with Yale, brief though they were, and I should be guilty of gross ingratitude if I failed to take advantage of this opportunity to thank you for the friendly interest you have shown in keeping me in touch with the class during the past 25 years. It has been a constant source of pleasure and inspiration to me. Wishing you the success you so richly deserve with the class book and affirming anew my loyalty to Yale and to the Class of 02. I Am Yours Truly, SL Brooks.” (Courtesy of the Yale University Archives – MSSA RU 0830, Series I, b158, Brooks Letter).

Two years later the Courant notified readers that Samuel Leon Brooks of 27 Mather Street died at the Hartford Hospital after a six-month illness. Brooks was reported to have spent the last 10-20 years of his life employed as a waiter at the Hartford Club (Hartford Courant, 1929-09-14). Undoubtedly, he must have crossed paths with former classmates over those years. Brooks is buried in a Diggs family grave site in Hartford.

Samuel and Lucy Brooks’ daughter, Julia (m. Saunders), appears to have died childless in 1990 in New York City, working as a maid.

There is no way of knowing all the challenges Samuel L. Brooks faced and why the promise of his youth led him to “humble paths,” but race barriers doubtlessly contributed to his challenges. Brooks, however, cracked at least one color barrier in Danbury, Connecticut, and his abilities allowed him to achieve acceptance into two illustrious New England educational institutions. This was no small feat given the headwinds he faced.

The entire text of Devlin’s February 28, 2000, article in the News-Times is reprinted below:

DHS’ First Black Graduate Left Mark

It’s still black history month, and the story of Danbury High School’s first black graduate deserves telling. The old Evening News, predecessor of the News-Times, devoted considerable coverage to the event in 1893. The graduate’s name was Samuel L Brooks, and what makes his story unusual is not just that he was Danbury High School’s first black graduate. He was also voted most distinguished in his class and went on to attend Yale University. In 1893, Brooks was chosen to read his essay at the graduation exercises. At the time, the senior who wrote and delivered the best essay won a $10 prize. School officials made it a point to dispel to the evening news reporter any suspicion of what would later be known as tokenism. “The prize, which is the highest honor within the gift of the high school committee, was awarded to Mr Brooks because he had earned it, and not because of sentiment or other influences,” They told the reporter at the time. Brooks was clearly considered to be a promising Young man: “he leaves a good impression,” the Evening News account reads: “his manner is modest and unassuming. His eyes sparkle with intelligence, and his voice is round and full and pleasing.” Indeed, the delivery of his essay was one component of the judging.

Brooks was reportedly planning a law career which he had already begun to study. When Brooks was growing up there were probably fewer than 200 black persons in Danbury, about 1% of the population. There was no legalized segregation as in the south, but the small community found itself set apart by custom in many ways. Blacks found work and some owned homes all could attend local public schools like everyone else. Samuel Brooks’s Father William Brooks was one of those who did well. He was a veteran of the Civil War from Maryland who moved to Danbury from Washington DC soon after the war ended. In 1874, he purchased a building at 43 Elm Street for his Barber shop. He also ran an employment agency from the house.

“A man of independent means steady and industrious and a good citizen.” He prospered according to his 1918 obituary he was known for driving “one of the finest horses owned in the city,” but local blacks were daily reminded of their difference in color they had to sit in the balcony of the Opera House and were given exclusive use of the local skating rink one night a week. They were never fully part of the local society. The high school was then a small part of local society, but growing in importance. In 1893, Danbury High School had only been around for 17 years. Only a tiny percentage of Danbury use even attended High School, let alone graduated. Most boys went into work or business at an early age. Brooks’s tiny graduating class of 1893 had 12 members, only four of them boys. Classes were held on the third floor of the Union Savings Bank building on Main street. Graduation exercises were held in the oppressive heat of late June on the stage of the old Taylor Opera House at Main and West streets. A year after Samuel Brooks’s graduation an item about him appeared in the news again, this time it was reported that he and his partner had won the cakewalk dance given at the Ridgewood Social Club, a place where many young black people from Danbury worked at the time. A year after the dance, young Samuel Brooks was reported to be spending a year preparing for college at the prestigious Phillips Andover Academy in Andover mass, and the following year, 1896, he began his freshman year at Yale, but what happened to him after that is a big question mark. One that perhaps will be answered in time. Nonetheless, his local upbringing and academic distinction he won in the Danbury area afford a small window on one part of the area’s past.

Readers of this blog will notice recent mentions of composer Richard Moryl, who, as stated in an earlier post, lived in Danbury for a time in the 1970s. For three decades, Moryl served as a music and composition professor at WestConn in Danbury, CT, as well as the University of Connecticut and Smith College.

Readers of this blog will notice recent mentions of composer Richard Moryl, who, as stated in an earlier post, lived in Danbury for a time in the 1970s. For three decades, Moryl served as a music and composition professor at WestConn in Danbury, CT, as well as the University of Connecticut and Smith College.

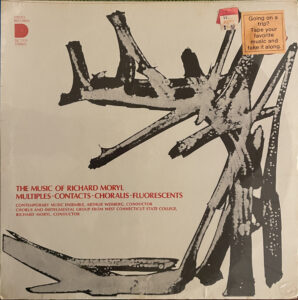

Essentially, the interest in Moryl began with a score for an experimental piece that was finally cataloged after it had been lying around untouched for many years (another story). Intrigued by the score, the archivist (me) began looking for music in WestConn’s collection by Moryl. An interesting and exciting revelation that came out of that search was that Moryl worked with WestConn students in the 1970s for one of his recordings. Unfortunately, that LP which was listed in the Library’s catalog was missing. Fortunately, that same archivist was able to find for sale a sealed copy of the record online. It was purchased and donated to the archives.

What we have is an interesting artifact that shows the intersection of this college with cutting edge composers. It also bears a Peaches Records price tag ($.49) – truly an artifact from the 1970s. Click the image for more information on the record.

Among the Ruth Steinkraus-Cohen Papers is a piece of sheet music that was cataloged today entitled: A second sett of favorite airs and a march : arranged as rondos for the piano… Is this her autograph? It appears to be the initials of this Bohemian female composer from the early 19th century.

There’s this gem released in 1972 of late 60s recordings from CT-born composer, Barbara Kolb, and Richard Moryl, who lived in Danbury for a short time. The album is pretty iconic as well.

There’s this gem released in 1972 of late 60s recordings from CT-born composer, Barbara Kolb, and Richard Moryl, who lived in Danbury for a short time. The album is pretty iconic as well.

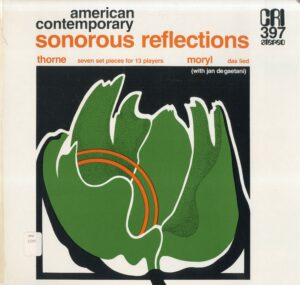

And this 1978 recording of pieces by Francis Thorne and Richard Moryl – Sonorous reflections.

For more Richard Moryl – see: https://archives.library.wcsu.edu/omeka/items/show/7982

Richard Moryl composed: Madrigals (so, that I would like to die) : for chamber choir (playing perc. instrs.) and amplified piano in Danbury between 1973 and 1974.

Moryl (b. 1929, d. 2018) attended Columbia and Brandeis Universities and was the founder and director of the Charles Ives Center for American Music (CICAM). Later he founded and directed the New England Contemporary Music Ensemble.

Here is a digitized version of his piece, Madrigals (so, that I would like to die) : for chamber choir (playing perc. instrs.) and amplified piano

Just 4 days before the armistice on November 11, 1918 at 11AM, Mrs. Hawley, who had learned of the death of her son a couple of weeks prior, received a condolence letter from her sister. Because of the military operations involving U.S. troops in the fall of 1918, this letter was one of many similar pieces of correspondence that were sent to American families that November. After the Second World War, November 11th changed from Armistice Day to Veteran’s Day.

https://archives.library.wcsu.edu/omeka/items/show/2578

George B. Hawley Papers

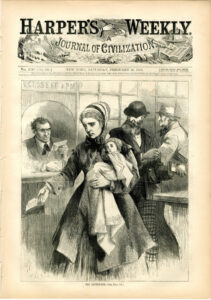

The devastating tragedy in Libya resulting from failing dams reminds us of the number of dams in the Danbury area. In 1869, the Kohanza dam broke in Danbury, which resulted in water and ice crashing into downtown Danbury. According to Harper’s, 13 were killed and it wrought $100,000 in damages (something like 2.2 million today). Take a look at the Harper’s Weekly that reported on the local event.

The devastating tragedy in Libya resulting from failing dams reminds us of the number of dams in the Danbury area. In 1869, the Kohanza dam broke in Danbury, which resulted in water and ice crashing into downtown Danbury. According to Harper’s, 13 were killed and it wrought $100,000 in damages (something like 2.2 million today). Take a look at the Harper’s Weekly that reported on the local event.